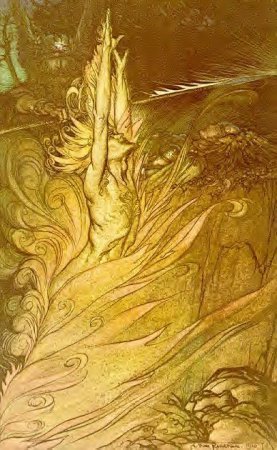

Loki, Father of Strife

Written by Alice Karlsdottir, © 1991.

| |

Loki is usually portrayed as a beautiful but evil god, quick-witted and well-versed in cunning. Some of the epithets for him given by Snorri Sturluson in the Prose Edda include "forger of evil," "the sly god," "slanderer and cheat of the gods," and "wrangling foe." (Snorri Sturluson, The Prose Edda, Arthur Gilchirst Brodeur, trans. (New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation, 1916), pp. 114-15) He is sometimes thought to have been a fire demon in his early forms. His father was Farbauti ("Cruel Striker"), no doubt some kind of storm giant or lightning deity. his mother is called Laufey ("Leafy Isle") or sometimes Nal ("Needle"), and Loki is always referred to by the matronymic Laufeyarsson, rather than by his father's name, as was the common practice at the time these myths were written down; perhaps this indicates some doubt about who Loki's father really was. Loki is one of the race of Jotuns, the giants who are the sword enemies of the Aesir. Although it is not uncommon to find giantesses marrying into the Aesir or Vanir, Loki is the only male giant to be found among them. He is said to have gotten in by swearing the oath of blood brotherhood with Odin, the chief of the gods. After this very solemn ceremony, Loki not only is accepted into Asgard, the abode of the Aesir, but is admitted into their council of law as well. Once in Asgard, Loki proceeds to lead a long and colorful career of getting the gods into and out of trouble through his cleverness, cunning, and love of mischief. Along the way he sires two legitimate sons by his wife Sigyn (or Siguna) and three "monsters" by the giantess Angerboda. He is also mother to Odin's prized eight-legged horse Sleipnir (we'll explain that one later). Finally he contrives the murder of Balder, the most beloved deity, and then gets drunk at a banquet and insults all the gods. Eventually he goads the Aesir into chaining him up under the earth. Here he can cause no more trouble (except for earthquakes) until Ragnarok, the Twilight of the Gods, when Loki will lead the forces of doom and destruction against Asgard and the world as we know it will come to an end. Even this brief description of Loki raises many questions. He really can't be dismissed as an archvillain and nothing more. If he's so evil, how in the world was Odin, the all-wise, persuaded to mix blood with him? Why does the brave and honorable Thor continue to hang out with him long after he has proved himself something less than trustworthy? If Loki is such a vile creature, why is he now, as he has always been, such a damned appealing fellow, continually turning up in more stories, legends, and folk traditions than any other god? It seems likely that Loki's original character was less wicked than it was later portrayed. The influence of Christianity on Norse culture doubtless had an effect on the figure of Loki, who gradually became more and more evil. The concept of a deity both helpful and destructive (and bawdy to boot) was just not compatible with the changing mythology. Although many of Loki's actions appear evil at first glance, when viewed symbolically they take on a different meaning. Loki must be considered within the old Norse concept of the world, where good and evil were not the polarized absolutes they have come to seem. He ultimately appears as a powerful and compelling personality underneath the buffoonery, and if Loki was considered part of the Aesir pantheon, then he probably belonged there, serving a necessary function in the Norse mythos. The kidnapping of Idunna, the goddess of youth (during which Loki aids the storm-giant Thjassi), and Loki's theft of the love-goddess Freyja's necklace are both similar in motif. In each, a goddess or something belonging to her is taken away by Loki and later returned (albeit usually because the other gods threaten to kill Loki if he doesn't). These actions can all be seen as representations of the cycle of the seasons, the winter-summer myth. Loki emerges as one who turns the wheel of the year--in other words, as a force of change. Change is not always pleasant, but most will agree it is necessary now and then. This was no small undertaking. In effect it gave Loki the same status he would have had if he really were Odin's brother, and, once made, this type of oath could not be broken. It is interesting to note that one of Odin's many names, Helblindi, is the same as that of one of Loki's obscure and little-mentioned brothers. Odin and Loki are most definitely related god-forms -- clever and cunning, versed in magic, connected with winter and death, both with a hint of the dark side about them, shape-changers, sex-changers, travelers. It would be more of a puzzle if they hadn't developed some sort of relationship. Jungian psychology claims that everyone has a "shadow" side, a darker aspect to his or her nature, which can either be recognized, accepted, and integrated, or ignored and denied, in which case it becomes projected outward as the evil "other." In Norse legend Loki, instead of being cast into outer darkness, is brought home by Odin. One can see the union of Odin and Loki as symbolic of the forces of reason and order (the Aesir) accepting and integrating the symbol of the chaotic and primal (Loki) rather than attempting to avoid or destroy him. As a result of this process of integration, the Aesir can keep an eye on Loki and can periodically force him to repair his mischief. He is also available to benefit the Aesir; many of his tricks are to help them, indicating that the dark side has potential resources the rest of an entity can use. Lastly, Loki serves to initiate various cycles in the development of the Aesir, including the culmination of their development: their death in Ragnarok. As two opposing forces on a wheel will cause it to spin, the union of Odin and Loki serves to keep the universe in equilibrium. Either force alone would produce total destruction or, conversely, stagnation. By working together, they keep the wheel of time moving. Why should this be? For one thing, both gods have a connection with fire. Loki, as I've mentioned before, is said to have developed from an ancient fire demon. Thor, the god of thunder, causes lightning with the sparks emitted from his chariot wheels or from his thrown hammer, and his eyes glow like coals and themselves throw off sparks when he's angry. it is sometimes suggested that Loki represents the lightning that accompanies Thor's thunder. At any rate, Thor is certainly astute enough to realize he can use someone with quick wits to help him on his escapades. Another trait Thor and Loki have in common is a mutual inclination to disregard authority. What, you say? Good old law-abiding Thor a renegade like Loki? Well, the fact is that in many myths Thor often shows himself to be outside the normal framework of society. In several stories the Aesir are plagued by a giant visitor whom they cannot kill because of some vow or because he is protected by the laws of hospitality; then Thor appears, declares he is bound by no vows, and bashes the interloper's head in. One instance of this is the story of the giant who disguises himself as an ordinary laborer and offers to erect a wall around Asgard in return for the sun, the moon, and the goddess Freyja. he tricks the gods into letting him use the aid of his horse, which is really a magical creature, and he nearly succeeds in completing his task by the deadline. However, he is ultimately cheated out of his wages by Loki, who turns himself into a mare and lures the stallion away (Odin's horse Sleipnir is the result of this trick). The threatening giant is supposed to be under safe-conduct despite hit attempted deceit, but Thor is not one to hold to loopholes in the law and quickly dispatches the intruder. Unlike Loki, Thor is a model of personal honor, but they both seem to disdain the conventional laws of authority. Then there is the story of Thor's fishing trip. he sets out with the giant Hymir, using an ox head for bait, and hooks the Midgard Serpent, which surrounds the world. Before Thor can kill it with his hammer, Hymir cuts the line and it sinks back in to the sea. Now there is some evidence that if the serpent let go of its tail and left its place at the boundary of Midgard (our world), the world would end. If this is the case, Thor's rash desire to eradicate the forces of darkness would have the effect of altering the balance of the universe and bringing on destruction prematurely. It is the tendency to want to change the status quo that gives Thor and Loki a point in common. Both of them are forces of death and of creative destruction. But Loki's most important function for Thor is as his antagonist. In many ways Thor is the most human of the gods; he is a sort of Everyman figure, and his experiences often symbolize the struggles faced by ordinary people. Yet Thor gets a little full of himself at times, and Loki sees to it that he is made to feel a bit foolish now and then, just to keep him on his toes. It's pretty hard to be an omniscient tyrant with someone like Loki around to trip you up occasionally. Thor needs this kind of irritation to make him think; we all do. A glimmer of this august side to Loki appears in the story of Thor's visit to Utgard-Loki, "Loki of the outer world," a giant ruler who is a master of magic and illusion and who makes Thor look like a fool in a series of stacked competitions. When Utgard-Loki at last reveals his deceptions to Thor, the giant and his kingdom vanish in the mists before Thor can lift a hammer. Because Loki accompanies Thor on this journey and is also tricked by the giant king, he is generally not suspected of having any connection to him. But doesn't the fact that these two giants have the same name make you a little bit curious? The idea of deception is present in both of these Lokis, and being in two places at the same time wouldn't be all that difficult for Loki. Certainly he isn't above making a fool of himself as well as of everyone else. The story usually heralded as 'where Loki first went wrong" is the account of his three monstrous progeny, gotten on a giantess known as Angerboda ("Anguish-boding"). These children are Hel, the goddess of death, Jormundgard the World Serpent, and the Fenris Wolf. The fact that Loki begot these creatures of death and darkness is supposed to show the true malevolence of his character, and it is true that these beings are some of the chief forces of destruction at Ragnarok. But let's examine what each of them might represent. Hel, the goddess of the underworld, is generally depicted as parti-colored, being one half living flesh and the other half a decayed corpse. In the Eddas there is a description of her abode, where her table is called "Hunger" and her bed "Sickness." But the sagas and Eddas also have descriptions of people sharing Hel's bed after death, of her halls laid with rushes and her benches strewn with gold, and of her mead-vats brewing away. There is not much evidence that Niflheim, her realm and the abode of the dead, is a bad place to wind up. It is not an abode of damnation, but merely a place where just about everyone goes when he or she dies, except for special sorts who wind up in Valhalla or some other realm. Death is not pretty, so neither is Hel; nor is it a thing of evil or dread, unless you insist on seeing it that way. Death is a natural part of the cycle of life, and Hel and her quiet, peaceful kingdom seem to me to be anything but threatening. The Midgard Serpent, a huge snake that lies with its tail in its mouth, encircling our world entirely, is a little less palatable. It wakes up in time for Ragnarok and manages to kill Thor with its venom just as Thor is bashing its head in. But except for this battle, it doesn't do anything particularly sinister; on the contrary, there's a certain sense of order created by this scaly boundary between us and all those other beasties out there in the other eight worlds (Norse myth holds that there are nine in all). There is also a sense of power in the image of a serpent with its tail in its mouth; in fact it is a common symbol in many cultures (cf. the serpent symbolism in kundalini yoga). With the awakening of the serpent at Ragnarok, this power is released and the world as we know it ceases to exist. Then there's the real nasty, the Fenris Wolf, so ravening and dangerous that the gods had to chain it up with sword holding its jaws open, the god Tyr losing a hand in the process. The Fenris Wolf seems to exemplify sheer, raw, uncontrolled power which must be kept in check at all times. At Ragnarok he bursts his bonds and kills Odin; Vidar, Odin's silent son, then appears and rips the wolf's jaws apart. Some old carvings show a huge beast being ripped apart and the swallowed god emerging from its belly. Some think the original legend was of a god eaten and then resurrected, the whole thing being a kind of shamanic journey. (It is interesting to note that Tyr is also killed by being swallowed by Garm, Hel's dog, during Ragnarok.) Although Odin and Tyr are not actually depicted as being reborn, the children of the gods do survive Ragnarok to begin the new age -- much the same thing in the Norse view. Although the myth of Balder's death is well-known, the extent of Loki's responsibility for his murder is not as cut and dried as it seems. In the myth, Hodur, Balder's blind brother, is guided by Loki to throw a magic mistletoe dart which kills Balder. later, when the gods try to bargain with Hel for Balder's release from the underworld, an old giantess, who is usually assumed to be Loki in disguise, thwarts them. Balder remains in the realm of death, and after Ragnarok, as Odin's heir, he becomes the new lord of the Aesir. Many mythologies have a slain god in them; the real problem with the Balder story is that he doesn't get resurrected the next spring. So although he is often depicted as an agricultural or solar god, he doesn't really fit into these roles, since he lacks an annual cycle of death and rebirth. Instead the death of Balder can be seen as an initiation myth, a shamanic self-sacrifice to gain insight and knowledge, much as Odin sacrifices himself on the World Tree to win the runes. It was common in those days for the son of a chieftain to have to prove himself by some rite of manhood, often including a symbolic death. In the long run, Balder doesn't seem to lose out by being killed; on the contrary, he trades his innocence for knowledge and reappears after Ragnarok as a much more powerful and majestic figure, the new ruler of Asgard. Maybe Loki did him a favor by instigating his death. It is necessary here to talk about Ragnarok. The Norse world-view hinges on a sense of cycles of growth, a fact that is not always understood when discussing the "end of the world." It is understandable, though unfortunate, that the concept of Ragnarok has been confused with certain Christian ideas about Armageddon. There are no absolute forces of evil and good in the Norse cosmogony (except for those created by Christian hybrids), and Loki is not another Satan. Ragnarok is more like the end of an eon, the destruction of a way of thinking and living, to be replaced by a new cycle, a new world, and new gods, all built on the foundations of what has gone before. There is no sense that the new order is inherently better than the old, or that the old ways were wrong. It is just time for a change. Ragnarok is not a one-time cataclysm, but a recurrent happening, as gods and people evolve ever upward and outward. The survival of the Aesir and Vanir children implies the reincarnation of the entire pantheon, with the same forces now appearing in different combinations. Balder, emerging from Niflheim at last, takes over as the new All-Father. The world of Odin now gives way to a new world, a new outlook, new concepts and goals. This is seen as an opportunity for growth, development, and change, not as disaster; it is a natural part of the universal cycle, as death is a natural part of an individual life. Loki is the god of change who sets this all in motion; he is resisted, because radical change is never welcome, and because the struggle of Ragnarok is necessary to liberate the new forces. Loki forces the cycle to its conclusion; he is the god who turns the wheel of the universe, though he too is involved in the destruction. Conflict, dissension, struggle, exertion, endeavor -- these are the things that move the universe. Without them we would be as stones, unmoving, uncaring, untroubled. Loki is the force that disrupts out lives, that stirs us from the comfort and peace of our firesides and forces us out to battle. He can turn our world upside down and change every idea we hold dear, but with him in our lives we need never fear boredom.

|

|